Getting Beyond WEIRD

The authors proposed that wide variations exist in how different populations perceive things, behave, and draw their motivations. They set out to test their hypothesis by conducting research with differing populations and cultures around the world.

[imageframe lightbox=”no” style_type=”none” bordercolor=”” bordersize=”0px” stylecolor=”” align=”right” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ class=”” id=””][/imageframe]

Marketing and advertising are both firmly rooted in the social sciences. Consciously or not, we employ the principles of psychology, sociology and economics in developing campaigns and, most certainly, in conducting and applying market research and statistical analytics. Consequently, we can all benefit from the insights of a working academic paper published three years ago under the provocative title: The weirdest people in the world?*

In this case, “WEIRD” is an acronym that stands for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic. The authors of the paper – three professors from the University of Vancouver – called into question one of the fundamental assumptions of the social sciences: that the human brain is hardwired, making perceptions, behaviors, and motivations largely consistent across populations. In other words, cultural differences may affect how we interact, but things like visual perception, spatial reasoning, motivations and self-concepts, reasoning, and concepts of fairness, are consistent and transferable between societies and cultures.

The authors proposed that the opposite is true: that wide variations exist in how different populations perceive things, behave, and draw their motivations. They set out to test their hypothesis by conducting research with differing populations and cultures around the world.

Some examples

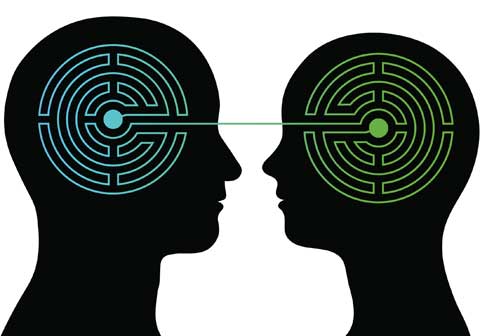

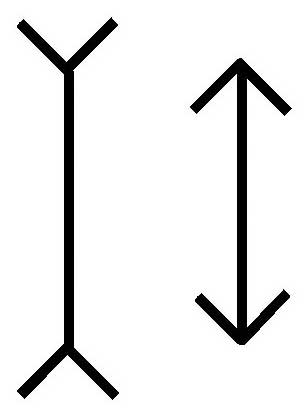

In their research they employed simple “games” that are commonly used in psychological tests. The simplest of these involves a familiar test of visual perception, the Miller-Lyer illusion, reproduced in the below illustration.

[imageframe lightbox=”no” style_type=”none” bordercolor=”” bordersize=”0px” stylecolor=”” align=”center” animation_type=”0″ animation_direction=”down” animation_speed=”0.1″ class=”” id=””] [/imageframe]

[/imageframe]

In America, most people perceive line A as being longer than line B; in less industrialized cultures people are more likely to see the lines as being equal, which they are. Why? The authors suggest that the prevalence of rectangular rooms with right angles biases our minds to see these as corners – and the brain perceives A to be farther away and must therefore be longer. In societies where hard angles and carpentered corners are rare, people do not have this bias.

In another classic experiment, the ultimatum game, a person is given an amount of money and told to share it with another in whatever proportion he or she chooses. Both know that if the second person refuses the offer, neither gets anything. In America, the offered split is usually 50-50, and it is common for the second person to refuse an offer of less to punish the unfairness. When tried within a rural Peruvian population, subjects almost always offered and accepted an unequal split, judging the refusal of any amount of money to be foolish, and greed being well within the rights of the person lucky enough to be given the option.

Using other games they tested a variety of perceptions, behaviors and motivations, including such fundamental concepts as fairness and moral reasoning. They ultimately determined that Americans were more the exception than the rule – even among Western cultures. Moreover, since so much experimental psychological research is performed using populations of undergraduate college students in North America (predominately WEIRD), they suggested that 96% of psychological studies came from countries that are representative of only 12% of the world’s population!

How does this apply to marketing and advertising?

In marketing we tend to be less academic and a lot more pragmatic, and we certainly accept cultural differences as important considerations in developing campaigns. Still, we are usually operating in a reasonably limited geographic market and deal with populations that are fairly homogenous in terms of perceptions, motivations, and codes of behaviors. The cultural differences that concern us are fairly superficial ones related to issues of ethnicity. And we are astute enough (I hope) to realize that an advertising platform that works here at home is unlikely to be as successful with rural, Peruvian sheepherders.

What we do need to be aware of are the potential effects of digital technology on succeeding generations of consumers. If, indeed, our brains are not hardwired, but subject to being influenced with regard to fundamental perceptions, motivations, and moral reasoning, how are different generations being affected by their respective relationships to digital media?

We use the term “digital natives” to refer to the young adults who never experienced a world without digital technology. We already know and accept that they, as a group, display attitudes and behaviors that differ markedly from earlier generations when it comes to such things as interpersonal connectivity, public display, sharing, cooperation, and feedback, to name just a few. In fact, they live in a world that is, for them, redefining many of the behavioral norms that govern communication and relationships.

Moving forward, if we presume that the digital culture is merely an overlay on the hardwired bedrock of the human brain, we do so at our own peril. And this first generation of digital natives is only the beginning; new technologies will affect new generations. Actually, we may need to adjust our definition of “generation” from a chronological to a behavioral context.

Marketing and messaging to each new behavioral generation will depend heavily on focused behavioral research, of course. To be successful, however, we must avoid the trap of assuming that the beliefs, values and attitudes underlying their behaviors are the same as the generation before them. We need to accept that what motivates them economically, intellectually and morally is not necessarily the same as what motivates us – the WEIRD ones.

* Henrich, Joseph; Heine, Steven J.; Norenzayan, Ara (2010): The weirdest people in the world?, Behavioral and Brain Sciences/Volume 33/Issue 2-3/June 2010, pp 61-83